The following is an article by investigative journalist Gracie Todd, published by KUOW on January 24, 2022, about Seattle’s lack of progress on its Vision Zero goals. We encourage you to read the article at kuow.org and to support its news reporting.

Pedestrian deaths climb in Seattle, despite city's pledge to eliminate them

With the force of a 3,000 pound metal box, a car knocked Dionna Glaze and her bicycle off the road. Having avoided serious injury, she felt lucky — but rattled to the core.

“Being hit by a car, you go through the different scenarios of what could have happened,” Glaze said.

Glaze bikes a lot less these days. She feels unsafe on Seattle’s roads.

That concern is justified. Increasingly, cars are killing pedestrians — people walking, rolling, or cycling — in Seattle. That’s despite the city’s 2015 adoption of Vision Zero, a project aiming to eliminate pedestrian fatalities. Seattle was among several cities in the U.S. to embrace Vision Zero — inspired by its success in various locations overseas — only to see pedestrian deaths rise.

“Fatalities are headed in the wrong direction — not toward zero,” said Allison Schwartz, the Vision Zero coordinator for the Seattle Department of Transportation. “So it’s not going as good as we would like it to.”

Pedestrian fatalities can affect anybody, but Seattle’s Black, homeless, and senior communities are disproportionately impacted.

Seattle’s pedestrian fatality rate was 150% higher in the five years after the launch of Vision Zero compared to the five years before, a KUOW analysis of SDOT data found.

Yet — cars have been hitting pedestrians less often. That means that a growing proportion of collisions are leading to death. That proportion was higher in 2019 than it had been in a decade, then it rose again in 2020, and yet again in 2021, KUOW’s analysis found.

To explain the rise in fatalities, we want to look at factors which make crashes more severe, said Steve Mooney, an epidemiologist at the University of Washington.

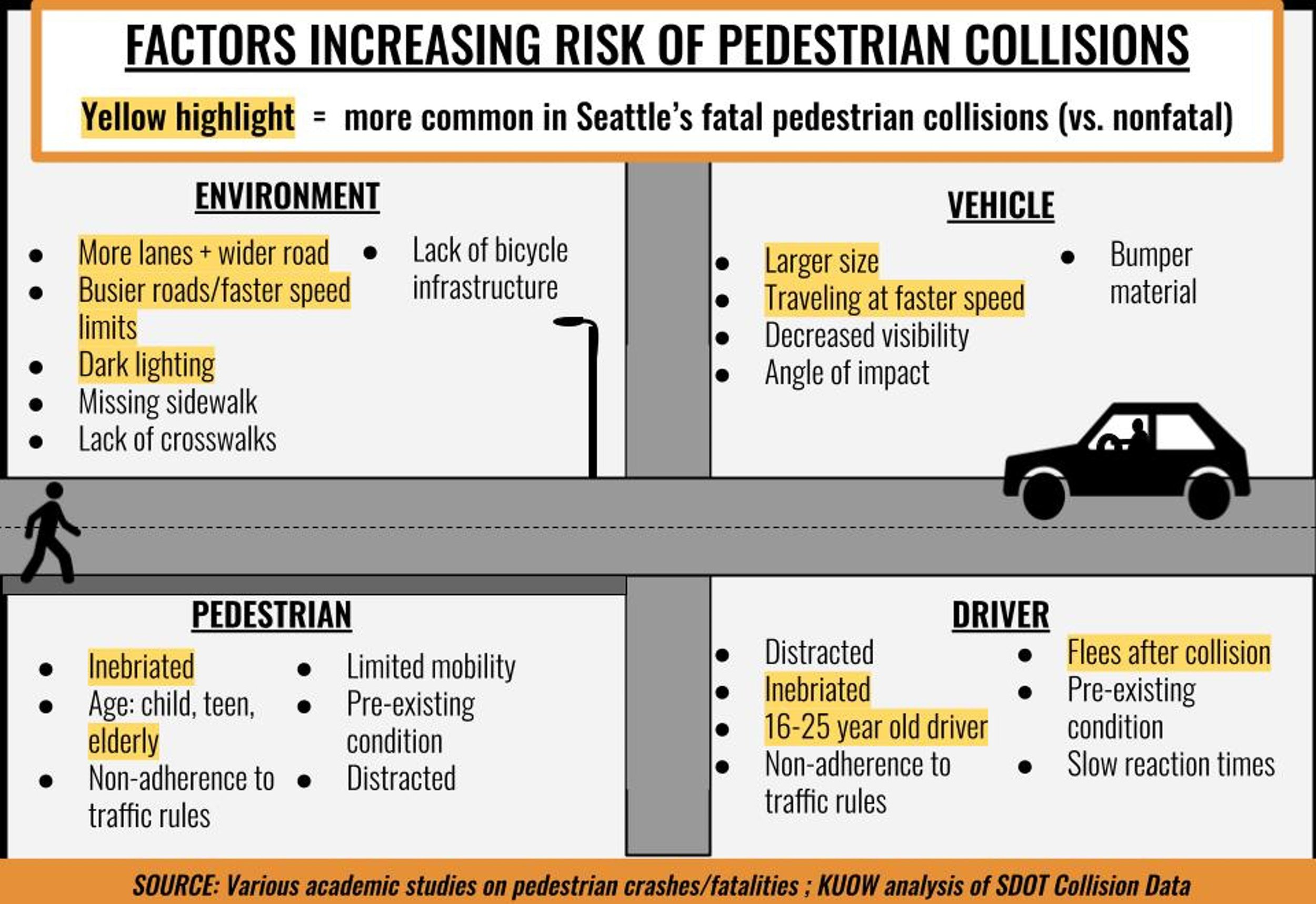

Several factors were especially common in Seattle’s fatal collisions between 2010 and 2021, compared to those which were not fatal, according to data from the state’s Department of Transportation.

Two factors were especially significant: larger vehicles and faster driving. Both are increasingly common on Seattle’s roads.

Larger vehicles impact pedestrians with more force, and are more likely to hit one’s chest versus their legs or pelvis, leading to more serious injury.

Passenger vehicles of all styles are getting bigger over time, according to a 2021 Environmental Protection Agency report. Moreover, larger models are becoming more popular, according to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

Buses and trucks are increasingly common on Seattle’s roads as well, according to SDOT reports.

Seattle wields little control over what people drive, but federal regulators could incorporate pedestrian safety into vehicle safety ratings. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has considered doing so for the last decade, but has taken no action.

Speed, along with size, matters a lot. If a vehicle hits a pedestrian at 30 mph, it is more than twice as likely to kill them than if it had been going 25 mph, according to an American Automobile Association report.

At least since the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020, vehicles are moving faster. That’s due to lighter traffic on the roads. Less congestion leaves more room for speeding.

Since 2015, Vision Zero has lowered speed limits on many Seattle roads. At 15 of 20 locations with speed limits reduced by 5 mph, and where data is available, most drivers slowed, too – but only by about 1 mph, a KUOW analysis of SDOT data found.

Dark lighting and impaired road users are also contributing factors in fatal collisions.

Mooney, the epidemiologist, said we shouldn’t overlook any factors which increase risk to pedestrians. Looking at trends over time is inherently nuanced when it comes to complex systems, he added. Individual risk factors can ebb and flow, and interact with each other.

Additionally, when it comes to public health, “understanding the reason for the trend is sort of one piece of the puzzle,” Mooney said. “It doesn’t change the fact that there’s a problem that we need to fix right now.”

Consistently, Seattle’s pedestrian fatalities occur on the busiest, widest, and fastest roads.

Roads where pedestrians died between 2015 and 2021 were, on average, nearly twice as wide as Seattle’s typical road, according to a KUOW analysis of SDOT data.

That analysis also found that arterials — roads split by a yellow line — accounted for over 90% of its pedestrian fatalities, but make up less than a third of Seattle’s road network.

Even more lopsided, over half of those pedestrians were killed on major truck routes, a subcategory of arterials that make up just 8% of Seattle’s roads.

Seattle's underserved communities have more than their fair share of these most dangerous roads. Census tracts with populations that are over 20% nonwhite have three times as many miles of major freight roads, on average, compared to less diverse census tracts, KUOW found when analyzing SDOT and Census Bureau data.

At the same time, those more nonwhite census tracts also disproportionately lack certain safety features, including sidewalks and pedestrian signals.

Inequities in other institutions, too, contribute to this disproportionality in pedestrian fatalities, including health care, mobility, zoning, and housing.

Around 20% of pedestrians killed in Seattle were considered unhoused, according to a 2020 SDOT presentation.

Mooney said that Seattle’s increasingly precarious housing situation may be contributing to the rise in pedestrian deaths, by forcing more people to live near the streets. He added that encampment sweeps may aggravate this issue, pushing people toward even “more marginal areas.”

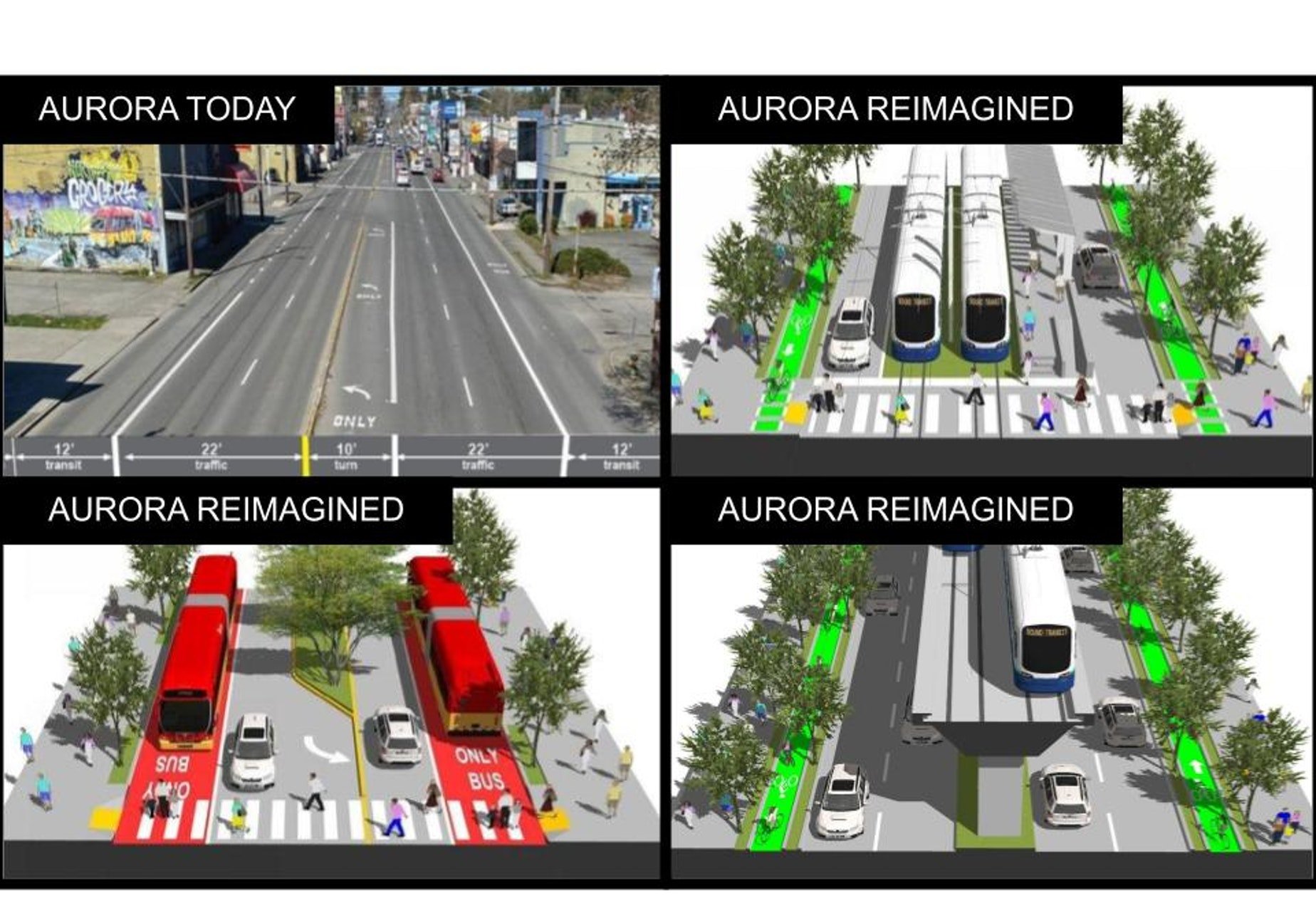

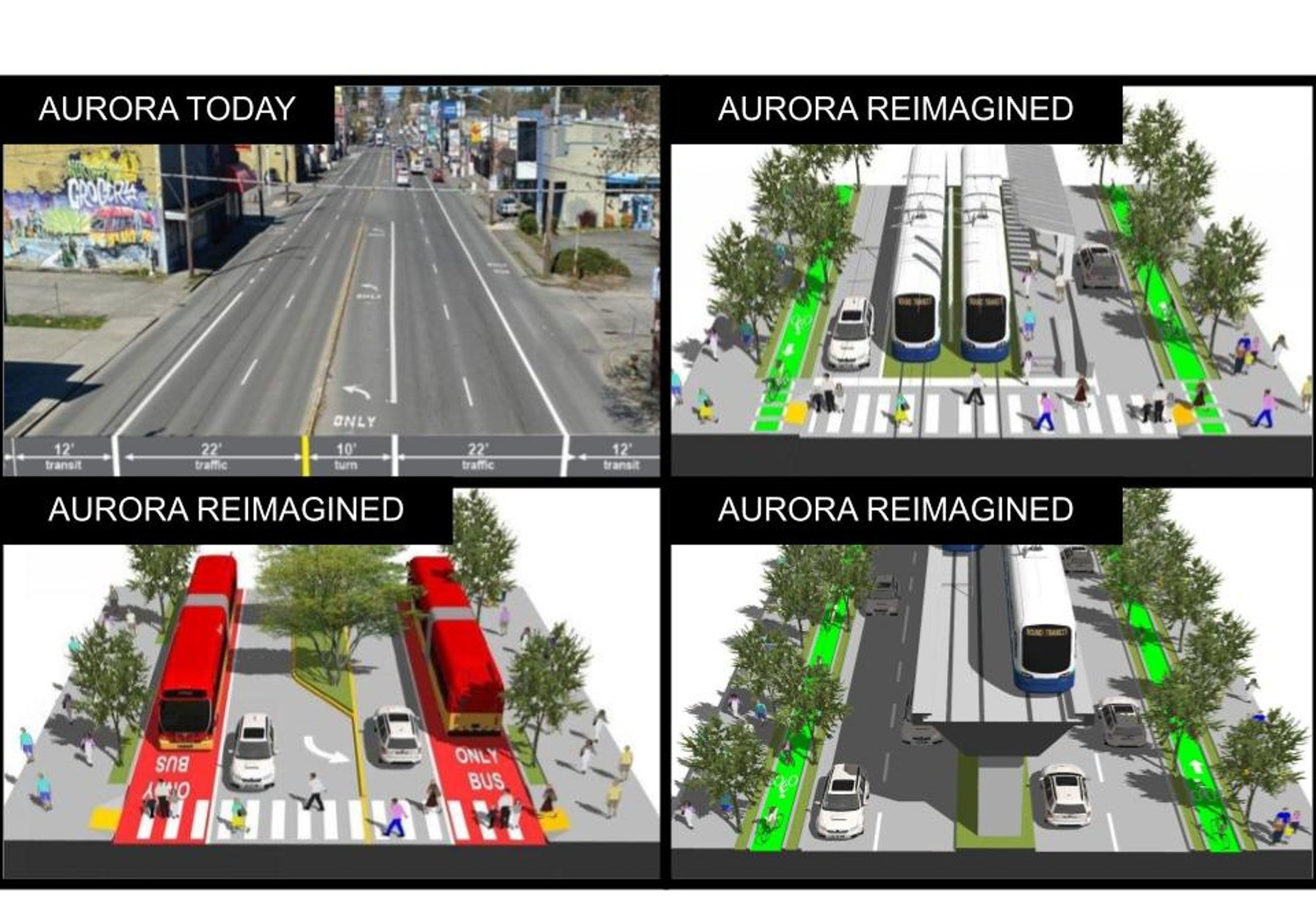

What Aurora Avenue North today, versus three designs proposed by Ryan DiRaimo, a member of the Aurora Reimagined Coalition.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF RYAN DIRAIMO

Aurora Avenue North is loud, busy, up to seven lanes wide, and dangerous. It’s the site of more pedestrian deaths than anywhere else in Seattle.

And, Aurora is more than that. Thousands of Seattleites call it home, local rock bands sing about it, and the Aurora Reimagined Coalition dreams about improving it.

“We want to see people able to connect to the other side of their community safely, on foot, on bike, or rolling,” said Tom Lang, a coalition member.

SDOT will launch a $2 million study this year to identify potential improvements along Aurora. Lang said that “we need something like this study,” but “we also are agreeing with a lot of the cynics in the community right now saying, ‘Another study?’”

The coalition hopes that — unlike several studies on Aurora over the last 20 years — this one will lead to concrete action.

“We want to see fewer people die,” Lang said.

Pedestrian collisions kill more Americans than fires, cervical cancer, or homicide by gunfire, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

This public health crisis stems from “a very strong car culture, and an anti-pedestrian culture, that’s taken root all over the country,” said Preston Schiller, a Civil and Environmental Engineering instructor at the University of Washington, and co-author of An Introduction to Sustainable Transportation.

Over many decades — and influenced by the automobile, oil, and asphalt industries — our roads were shaped to prioritize vehicle speed over pedestrian mobility or safety, Schiller said.

The solution? Redesigning the entire transportation system — roads, public transit, vehicles and land use — with safety for all road users at the forefront, Schiller said.

The philosophy is that while human error cannot be entirely eliminated, smart road design can reduce the harm those errors cause.

Changes to road design — including narrowing roads, building protected bike lanes, and converting intersections to roundabouts — can decrease vehicle speed, volumes, and conflict points with pedestrians.

Vision Zero has applied some of these strategies at various Seattle intersections and roadways, often with promising results. But these adjustments tend to be more moderate and geographically limited than pedestrian advocates would prefer.

“We need to take, unfortunately, a bit of a case-by-case approach while moving toward the bigger picture,” said Schwartz from SDOT. “We just need to scale it up and keep doing it.”

Vision Zero has also garnered criticism for strategies that focus primarily on individual behavior — especially enforcement, which can introduce additional issues and inequities.

In 2020, Seattle’s Vision Zero acknowledged these criticisms, and deprioritized, but did not discard, enforcement strategies. It vowed to focus less on road users, and more on the road system.

But broader changes face bigger barriers.

Receiving only a fraction of SDOT’s budget, Vision Zero must rely on outside funding for much of its work. And, only a handful of employees within the agency focus solely on pedestrian safety.

“There’s a huge culture shift that needs to occur,” Schwartz said, adding that while many within the department are committed to Vision Zero there is “room to improve” in pursuing all transportation projects with safety at the forefront.

Additionally, moving toward safer roads requires changes outside of SDOT’s reach.

Better land use planning is key to safe roads, said Jazmine Smith, who serves on the Queen Anne Community Council’s land use committee and co-chairs its transportation committee.

When housing is far from other needs, like the workplace, daycare, or grocery store, there’s more reliance on driving, which encourages more car-centric infrastructure, Smith said.

On the other hand, “when housing is built with everything you need right within a 15 minute walk, bike ride or roll… the priority shifts,” Smith said. “It’s going to be a safer and prettier street because that’s where the community interest is.”

Walkers and bikers on a road in Oslo, Norway.

CREDIT: COURTESY OF THE CITY OF OSLO, AGENCY FOR URBAN ENVIRONMENT

Oslo, Norway committed to eliminating pedestrian fatalities around the same time as Seattle. By 2019, the city – with a population similar to Portland, Oregon’s — recorded zero pedestrian deaths.

Sirin Hellvin Stav, Oslo’s Vice Mayor for Environment and Transport, said the key to that success was getting people to “leave the car at home and travel by foot, bike, or public transit.”

The city redistributed space from cars to pedestrians, expanded its public transit network, and committed to making pedestrianism “inclusive for people of all ages and abilities,” Stav said.

With fewer cars and more pedestrians, Oslo is safer for pedestrians and motorists alike, and also more sustainable, equitable, healthier, and friendly, Stav said.

“When you reduce space for the cars, there’s a resistance,” Stav said. “Then after a while, it was as good as gone. People saw the benefits, and almost nobody wants to go back.”

Diana Opong-Parry contributed to the reporting for this story.